Women in the Colony (2008-2011)

The colonial history during the period 1885 - 1962 in Congo, Rwanda and Burundi

The aim of the project "Women in the Colony" which was carried out from 2008 to 2011 at Cegesoma was to try to gain more insight into colonial history during the period 1885 - 1962 in Congo, Rwanda and Burundi from a gender perspective. The objective was to trace a collective image of western women in the Central African territories and to measure the impact of the presence of European women in the world of labour on colonial society, in day to day life as well as on the level of political orientations.

The results of this research project have been partially presented through contributions during symposia in Belgium and abroad, and in a series of publications, some of which are due to be published soon. In this article, we would like to present some of the main points that surfaced in the context of this study.

A prosopographical approach based on a database of some 5500 European women active in Belgian Congo and the Rwanda-Burundi territories has allowed to provide a much more varied and contrasted picture of the female western world, but also of the whole colonial society, then what academic contributions have been able to describe or what collective memory has been able to remember. A study of all the female public officials reveals implicitly a social class of lower-ranking civil servants and modest-income colonists who could not live on one salary to meet their daily requirements. A very different tale from the clichés that confronted the former colonists at their sudden return to Belgium in 1960.

The study of the registration sheets of some 2200 women employed at some point by the colonial state indeed reveals the existence of a real body of temporary staff with a precarious status, often competing with the class of Congolese 'Evolués'. A significant proportion of these European women had given up a paid job or a self-employed activity in Belgium to follow their spouses to the colony where they tried to contribute in the same manner towards the household expenses. Some were employed in the private sector in Africa before applying for a job in the public administration. It is probable that many did so after having worked for the public sector, but we lost their traces in the official archives.

While these women from modest backgrounds were active in the public administration from the interwar period on, a new group of European women appeared within the state administration during the Second World War, either to take the posts of male agents who had not been replaced, or to replace literate Africans in delicate posts (such as the censorship department). Between 1940 and 1945, the wives, daughters or widows of senior officials indeed joined those lower-ranking agents within what was then called “Auxiliaires volontaires féminines” (voluntary female auxiliaries). The great majority of these middle-class women left the administration at the outcome of the war but it would seem that they had paved the way to a more stable and qualified female employment. Between 1945 and 1960, a large number of social workers and teachers arrived in Congo, the former to work with the wives of the Evolués and the latter in the schools for European children. In this context a definite link can be established between the population growth in Western Europe and the opening up of the labour market to female employees from Belgium.

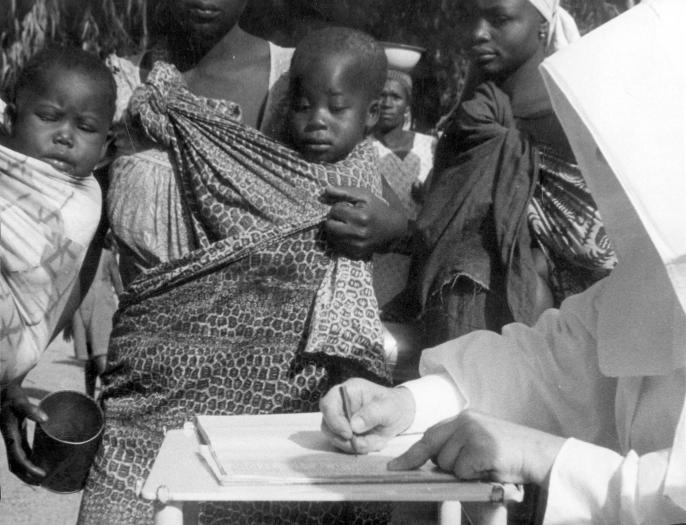

Our research did not only concern lay persons since the missionary world was quite influential in the Belgian colonial system. It is no surprise to learn that nuns, deaconesses and other protestant missionary women dedicated themselves with priority to the health and education sectors, but they also exercised the posts of workshop supervisors, agricultural workers and supervisors of construction sites. Thus, they were also employers of a crowd of adult and infant workers, and consequently were influential economic agents.

Furthermore, in the course of these charitable and economic activities, these missionary women found an opportunity to assert themselves vis-à-vis the male authorities, mainly missionaries, and to participate in various projects of the colonial state. The question of the relation between the missionary sisters and the colonial regime also deserved further examination. We have first of all applied this issue to the independent state of Congo, by trying to find out how catholic religious women and the wives of protestant pastors had experienced the impact of the policy of economic exploitation and the treatment of populations, and in which way they had contributed to it. This examination should be pursued also for the rest of the colonial period.

Thus, this long-term project opens up even more research avenues. It has proved to be not only instructive, but through raising questions about the colonial system itself, it has thereby transcended to a large degree the particular issue of gender.