Fascism in the CegeSoma Library (2) : the case of Belgium.

"Fascism in the CegeSoma Library (2) : the case of Belgium". Under this title, we invite you to discover the thirteenth theme of our series 'The Librarian's talks'. Each theme will be the occasion to dive into our collections and will be illustrated by a video and a text to complete the information contained therein.

Watch the thirteenth episode of our video series 'The Librarian's Talks : 13. "Fascism in the CegeSoma Library (2) : the case of Belgium".

As fascism became an essentially (but not exclusively) European issue in the course of the interwar years, Belgium would not be able to escape it. Still, for a large part of this period, the appeal of such a regime remained marginal. The attractiveness actually came in the 1920s for thousands of soldiers who fought in the First World War, who suffered emotional damage and struggled to find their way back into a normalised civil society. Their resentment was indeed voiced by parts of the ‘old Catholic right’ that had a hard time accepting the loss of its political monopoly when universal suffrage was introduced… A couple of names illustrate these fascist or fascist-leaning movements of the time: the Légion nationale, the Jeunesses Nationales, and later in Flanders the Verdinaso of Joris Van Severen. The economic crisis of the 1930s and the inefficiency of the Belgian parliamentary system caused a regain of interest in Belgian-style fascism and even a political breakthrough in 1936, when Rex and VNV entered parliament. But they were two distinct movements with regard to their identity politics: one was a proponent of the Belgian state, while the other rejected it and advocated for Flanders and the Greater Netherlands. And both joined forces in the collaboration with the Nazi occupant, which in the eyes of the public, ultimately blurred the lines between them...

As such and despite their eventual failure, they marked the memory of people, with Rexism and its excesses being much more demonised in the French-speaking areas than VNV in Flanders.

However, it took a long time to address the issue of fascism in a scientific manner, as the topic carried such a heavy emotional burden “in illo tempore”.

It was not until the 1960s that some historians addressed the issue, with all necessary dialectic precautions. While Jacques Willequet presented Les fascismes belges in a special edition of the journal Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (in April 1967), Jean Stengers delved into this curious political phenomenon with a rather neutral, catch-all… but misleading title (La Droite en Belgique avant 1940) in Courrier Hebdomadaire du Crisp (January 1970). But the most comprehensive study of Rexism was carried out, quite revealingly, by a French researcher and not by a Belgian one: Jean-Michel Etienne indeed penned Le Mouvement rexiste avant 1940 (1968).

It was not until the 1960s that some historians addressed the issue, with all necessary dialectic precautions. While Jacques Willequet presented Les fascismes belges in a special edition of the journal Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (in April 1967), Jean Stengers delved into this curious political phenomenon with a rather neutral, catch-all… but misleading title (La Droite en Belgique avant 1940) in Courrier Hebdomadaire du Crisp (January 1970). But the most comprehensive study of Rexism was carried out, quite revealingly, by a French researcher and not by a Belgian one: Jean-Michel Etienne indeed penned Le Mouvement rexiste avant 1940 (1968).

On the Flemish side, Eric Defoort wrote a voluminous research a few years later titled Charles Maurras en de Action Française in België (1978). Before them, the subject matter of fascism was the specialty of a handful of engaged publicists, mostly “anti”, such as Michel Géoris-Reitshof (Extrême droite et néo-fascisme en Belgique-1962). Nothing much changed during the 1970s, with the exception of the qualitative and useful studies by Etienne Verhoeyen in a series of Courrier du Crisp dedicated to L’extrême droite en Belgique, from 1974 to 1976: to this day these remain very reliable studies when addressing the issue in a post-war context, as they examine both Neo-Nazism and Catholic traditionalism.

On the Flemish side, Eric Defoort wrote a voluminous research a few years later titled Charles Maurras en de Action Française in België (1978). Before them, the subject matter of fascism was the specialty of a handful of engaged publicists, mostly “anti”, such as Michel Géoris-Reitshof (Extrême droite et néo-fascisme en Belgique-1962). Nothing much changed during the 1970s, with the exception of the qualitative and useful studies by Etienne Verhoeyen in a series of Courrier du Crisp dedicated to L’extrême droite en Belgique, from 1974 to 1976: to this day these remain very reliable studies when addressing the issue in a post-war context, as they examine both Neo-Nazism and Catholic traditionalism.

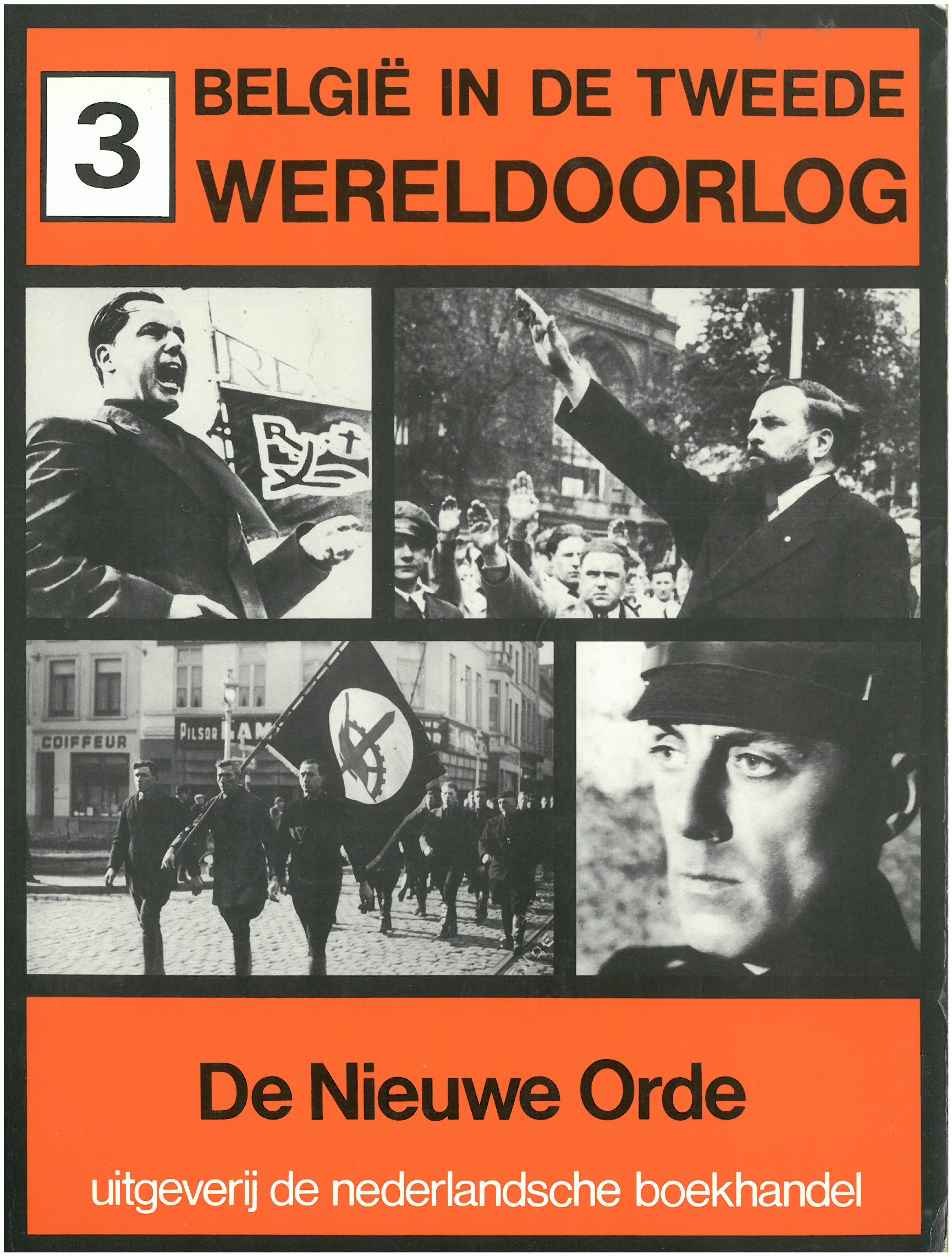

But these studies remained few in number. Yet the interest of the large public for this issue was revived in the 1980s with journalist Maurice De Wilde and his programmes that tried to dissect De Nieuwe Orde on public broadcaster VRT (1982).

But these studies remained few in number. Yet the interest of the large public for this issue was revived in the 1980s with journalist Maurice De Wilde and his programmes that tried to dissect De Nieuwe Orde on public broadcaster VRT (1982).  After that, publisher EPO, which was well-known in Flanders for its evidently progressive orientation, a number of researchers and investigative journalists (such as Walter De Bock) get interested in the far-right subject with L’extrême droite et l’Etat (originally published in Dutch under the title Extreem-rechts en de Staat in 1981) and Les plus belles années d’une génération (original title: De mooiste jaren van een generatie. De Nieuwe Orde in België voor, tijdens en na WO II, in 1982). This seemed to hit a nerve because afterwards publications appeared by Serge Dumont (Les Brigades noires-1983), Hugo Gijsels (Het Vlaams Blok 1938-1988), Manuel Abramowicz (Les rats noirs. L’extrême droite en Belgique francophone-1996). While this research was not lacking interest, “professional” historians were still not that much interested in the subject. Things started to move with the first successes of the Flemish-nationalist far-right Vlaams Blok, which was soon labelled by media as neo-fascist or fascist-leaning.

After that, publisher EPO, which was well-known in Flanders for its evidently progressive orientation, a number of researchers and investigative journalists (such as Walter De Bock) get interested in the far-right subject with L’extrême droite et l’Etat (originally published in Dutch under the title Extreem-rechts en de Staat in 1981) and Les plus belles années d’une génération (original title: De mooiste jaren van een generatie. De Nieuwe Orde in België voor, tijdens en na WO II, in 1982). This seemed to hit a nerve because afterwards publications appeared by Serge Dumont (Les Brigades noires-1983), Hugo Gijsels (Het Vlaams Blok 1938-1988), Manuel Abramowicz (Les rats noirs. L’extrême droite en Belgique francophone-1996). While this research was not lacking interest, “professional” historians were still not that much interested in the subject. Things started to move with the first successes of the Flemish-nationalist far-right Vlaams Blok, which was soon labelled by media as neo-fascist or fascist-leaning.

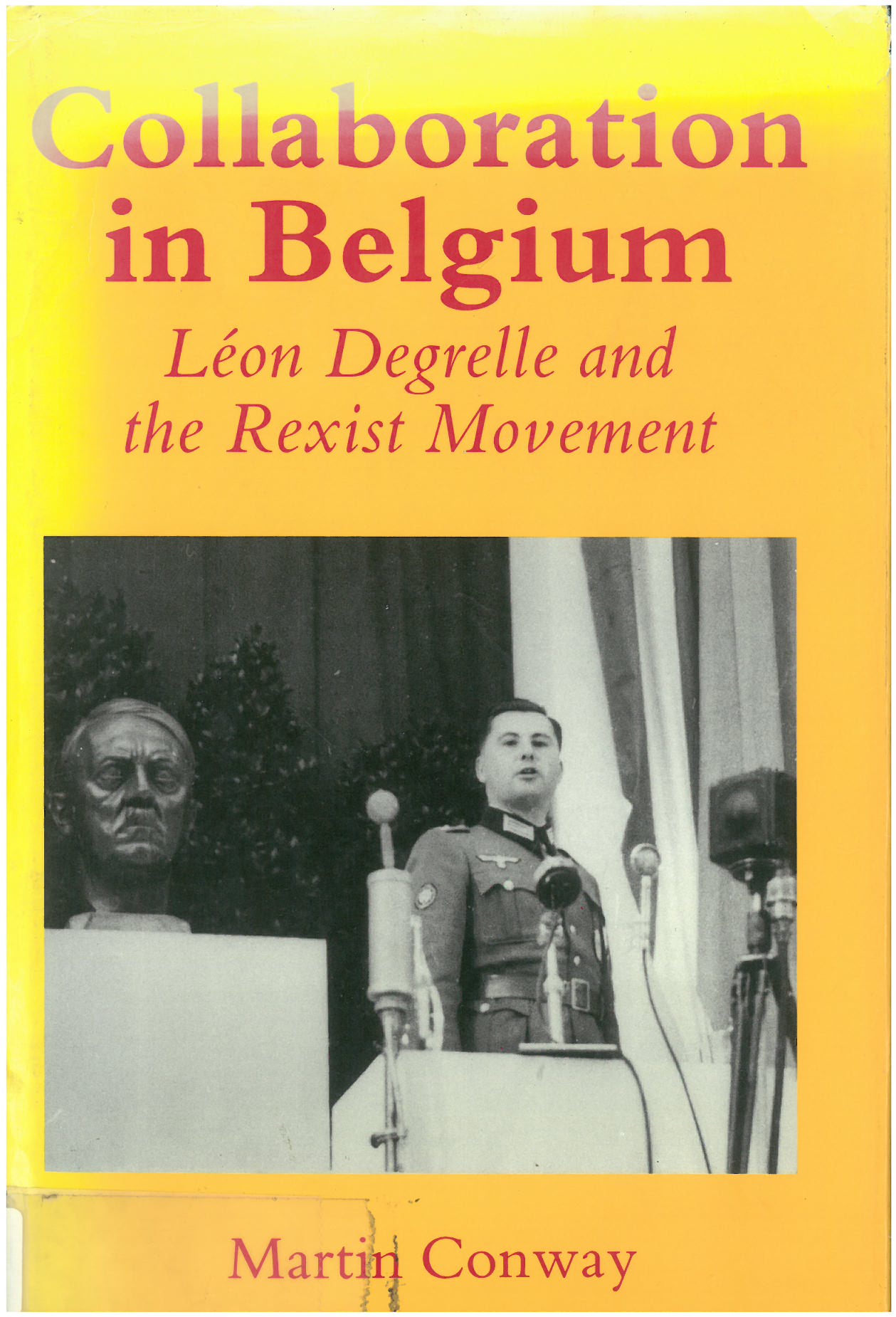

The result was that around CegeSoma, or rather around its predecessor CREHSGM, a number of worthy researchers, put down as such, came together and their corporative reflexions yielded two major publications: Herfsttij van de 20ste eeuw - Extreem-rechts in Vlaanderen 1920-1980 (1992) and De l’avant-guerre à l’après-guerre : l’extrême droite en Belgique francophone (1994). Both of them are collective works. And soon afterwards – coincidence? – two major works about the “historical” fascist movements were published by Martin Conway, Collaboration in Belgium. Léon Degrelle and the Rexist Movement 1940-1944 (1993) and Bruno De Wever, Greep naar de Macht. Vlaams-nationalisme en Nieuwe Orde. Het VNV 1933-1945 (1994). The first publication was soon translated into French and Dutch.

The result was that around CegeSoma, or rather around its predecessor CREHSGM, a number of worthy researchers, put down as such, came together and their corporative reflexions yielded two major publications: Herfsttij van de 20ste eeuw - Extreem-rechts in Vlaanderen 1920-1980 (1992) and De l’avant-guerre à l’après-guerre : l’extrême droite en Belgique francophone (1994). Both of them are collective works. And soon afterwards – coincidence? – two major works about the “historical” fascist movements were published by Martin Conway, Collaboration in Belgium. Léon Degrelle and the Rexist Movement 1940-1944 (1993) and Bruno De Wever, Greep naar de Macht. Vlaams-nationalisme en Nieuwe Orde. Het VNV 1933-1945 (1994). The first publication was soon translated into French and Dutch.

From this moment onwards, scientific publication flourished but without abundance, while more polemic publishing was ongoing for another fifteen years or so…It is worth underlining that while Vlaams Blok was regularly of particular interest for journalists and historians, its successor, Vlaams Belang, got much less attention. Maybe because it succeeded in fitting in with the political landscape in Flanders? Or because the political accusations it faced became unsubstantiated, more than two generations after the end of the Second World War? This seems to be the argument put forward in the latest work of Vincent Scheltiens and Bruno Verlaeckt, Extreem rechts. De geschiedenis herhaalt zich niet (op dezelfde manier), published in 2021.

From this moment onwards, scientific publication flourished but without abundance, while more polemic publishing was ongoing for another fifteen years or so…It is worth underlining that while Vlaams Blok was regularly of particular interest for journalists and historians, its successor, Vlaams Belang, got much less attention. Maybe because it succeeded in fitting in with the political landscape in Flanders? Or because the political accusations it faced became unsubstantiated, more than two generations after the end of the Second World War? This seems to be the argument put forward in the latest work of Vincent Scheltiens and Bruno Verlaeckt, Extreem rechts. De geschiedenis herhaalt zich niet (op dezelfde manier), published in 2021.